Kleiner Wall – the name of the island means something like small rampart. Berlin was established as a farming community back before anybody was bothering to write it down. Yet the area became important and the site of a city, for no other reason than it was easy to ford the Spree river. Spandau, the area near Berlin and where Kleiner Wall is located, sits on the Havel. Spandau features a citadel – one of the oldest and best-kept renaissance citadels in Germany – which sits right at the confluence between the Havel River and the Spree. It was important to control this gateway, so Kleiner Wall would have acted as a kind of first response, keeping track of who was travelling down the river toward Spandau, and then Berlin.

To be honest, I have only been inside the walls of the citadel Spandau twice. The first time was to go to a Renaissance Faire, which featured a mechanical dragon fifteen feet high that spat out fire. I felt like I was in Mad Max: Beyond the Reformation. It was amazing.

The other time was to see an exhibition of the statues that had been removed from the areas around the city. These statues had been taken down by a series of regimes over the twentieth century, acutely aware of the power of imagery in a cityscape. Some were removed by the Nazis, others by the Communists, some by the Capitalists, and many were removed after reunification in 1990. This was what I really wanted to see, for the feature of the exhibition was the image of 20th century communism himself – Vladimir Lenin. After the fall of the wall, there was such excitement and euphoria, that so much of the communist past was quickly removed. Some of it was done quite unceremoniously, as with the changes in street signs. Names like Wilhelm Pieck and Ernst Thaelmann were quick to disappear from sites around Berlin.

With Lenin, the story was a little more complicated. When they pulled the statue down from Leninplatz in Mitte, they changed its name to “United Nations Square,” trying to replace one concept of a world order with another. Yet the stranger development had to do with what happened with the statue after it was removed. Lenin’s likeness was taken down just two years to the day after the fall of the wall, with mixed reactions from the locals. It was a straightforward affair carried over eight days to disassemble the 19m statue. The new city government sold it as simply the next step to deleninize and de-communize Berlin. Yet when they cut him down, they sliced up his body into 120 different sections – man cut into pieces. They shipped him to the outskirts of Berlin, and buried him piecemeal like a modern day Osiris – scared that if they did not dismember him well enough, he just might come back.

His head ended up in a shallow grave in the southeast of the city. The pieces sat there for twenty five years, until finally someone decided to dig him up. When they did, they found him already fully integrated into the environment. They were unable to move the marble and steel, as a small group of threatened sand lizards had moved into his limbs and claimed it as their new utopia. Before they could move it, the city performed series of biological surveys to make sure they were not upsetting the new community literally living in the arms of Lenin.

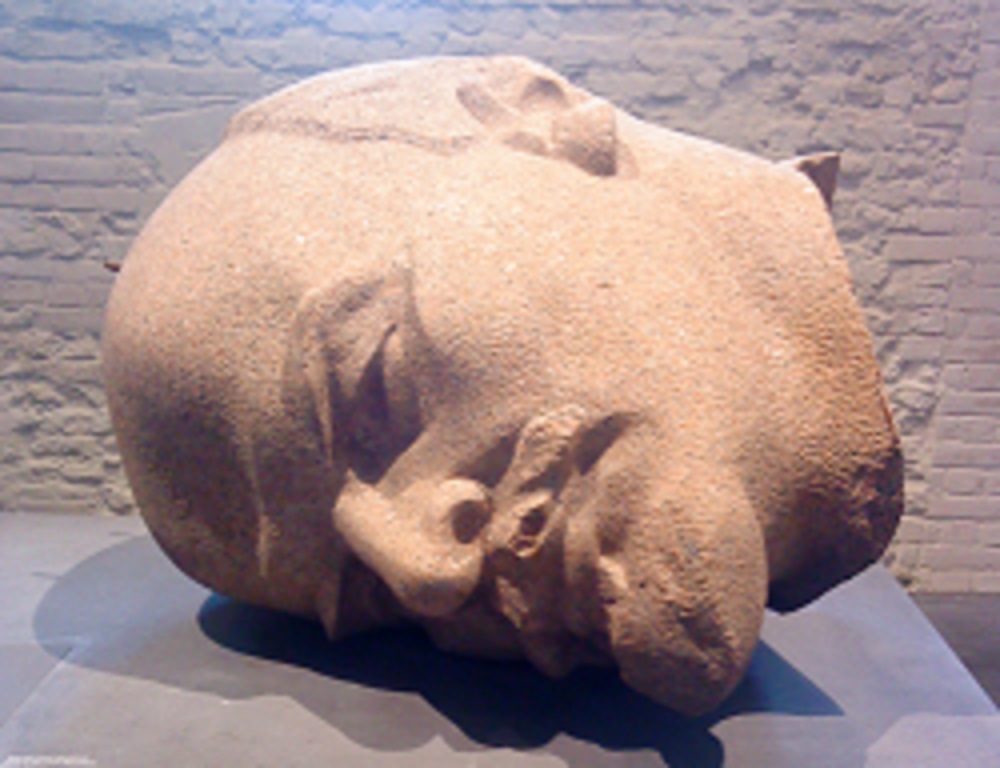

Once the survey was complete, and the lizards moved to a nearby nest, they collected his giant cranium and placed him in the citadel, locked behind those steep walls. they did not dig up the rest of his body, though. Perhaps it was superstition, perhaps it was disinterest, but his unincorporated head was the only thing that found its way into the museum. When I visited, I found the head at the back of the stables. I had to pass through room after room of famous Prussians that I had never heard of, most of them removed by the East German regime. It was only at the very back of the museum that I saw his countenance. Interestingly enough, he was the only statue left on its side, his blank eyes staring out, looking neither commanding or inspiring – just imposing.

Every other statue was placed correctly intact in the museum, rightly oriented. It was only the disembodied head of Lenin which lay on its side. Perhaps they were trying to make it seem like happenstance, as if the head had just fallen off that way. Yet it did not feel so casual, hidden so far in the back of the citadel behind all those forgotten generals – Set hiding Osiris’ body across Egypt. Yet his expression was as if he were simply gone, like they had forgotten his soul along with his body. Good thing Lenin didn’t believe in a soul.

We might not be quite done with him yet, though. A dismembered Osiris still gave birth to Horus, the ruler of Egypt for thousands of years. And I’m pretty sure that pointy beard is just waiting to come back in style.